Create

Mental Health and the Arts

For centuries, and across many cultures, “madness” has been associated closely with art and the artist. In the West, this association has since the 19th century been a romanticized one; often the artistic temperament is represented as teetering on the brink of mental and emotional instability. Edvard Munch, whose 19th-century painting The Scream has come to represent this connection perhaps more than any other work, famously wrote, “Without anxiety and illness, I am a ship without a rudder. My sufferings are part of self and my art” (The Private Journals of Edvard Munch:We Are Flames Which Pour Out of the Earth. J. Gill Holland, ed. UWisconsinPress, 2005).

One of the best-known artists associated with madness is of course Dutch post-impressionist Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890). Van Gogh famously became mentally ill while painting in the south of France. He spent time is psychiatric hospitals before committing suicide in 1890. His life and work lead us to ask,

Do we find his art more interesting because of his story of mental illness?

Do we then read his mental illness into his artwork, thus interpreting it differently than we would have otherwise?

The romaniticization of art has persisted into the present day. So-called “Outsider Art,” art by untrained artists identified as “mad,” often residents of psychiatric institutions, became increasingly popular throughout the twentieth century and into the twenty-first (see Daniel Wojcik, Outsider Art: Visionary Worlds and Trauma. UPress of Mississippi, 2016).

Yet such romanticization can obscure the actual pain of mental distress, pain that often is so intense that it can find no outlet in art or anything else. Contemporary discussions of the relationship between art and “madness” touch on both the dangers of such idealization and the potential of art to call into question definitions of “art,” “sanity,” and “insanity,” pushing beyond a clear divide between sanity and madness and between insider and outsider art.

For example, contemporary Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama, who has lately taken the international art world by storm, is hardly an

“outsider” artist, but her work and persona make no attempt to hide the effects of mental distress on her work. In an interview with Japanese poet and critic Akira Tatehata, who refers to her as a “magnificent outsider,” Kusama remarks openly that “The art world of Japan ostracized me for my mental illness” and insisted, “I rely only on my own imagination. I am not concerned with whatever they want to say about me.” In that same interview, Tatehata reflects on the ways art works and artists that have grouped together as belonging to particular schools in modern and contemporary art such as Surrealism, were “methodically legitimizing the world of those who possessed unusual visions such as yours” (Akira Tatehata et al. Yoyoi Kusama, Phaidon 2000). Tatehata’s interview with Kusama blurs the boundary between outsider and “legitimate” artist and raises the possibility that all art, in some way, plays at the edge between socially-agreed-upon “sanity” and “madness.”

Kusama’s work might lead us to think about how art addresses the boundaries between sanity and “madness” across cultures. Scholars have debated to what extent psychotic conditions such as schizophrenia cut across cultural boundaries and what form those conditions take within various cultures (Tanya Luhurmann and Jocelyn Marrow, Our Most Troubling Madness: Case Studies in Schizophrenia Across Cultures. UCPress, 2016). One question we might ask is,

When, if at all, do experiences of the unseen world fall outside the bounds of normally accepted spiritual beliefs and practices?

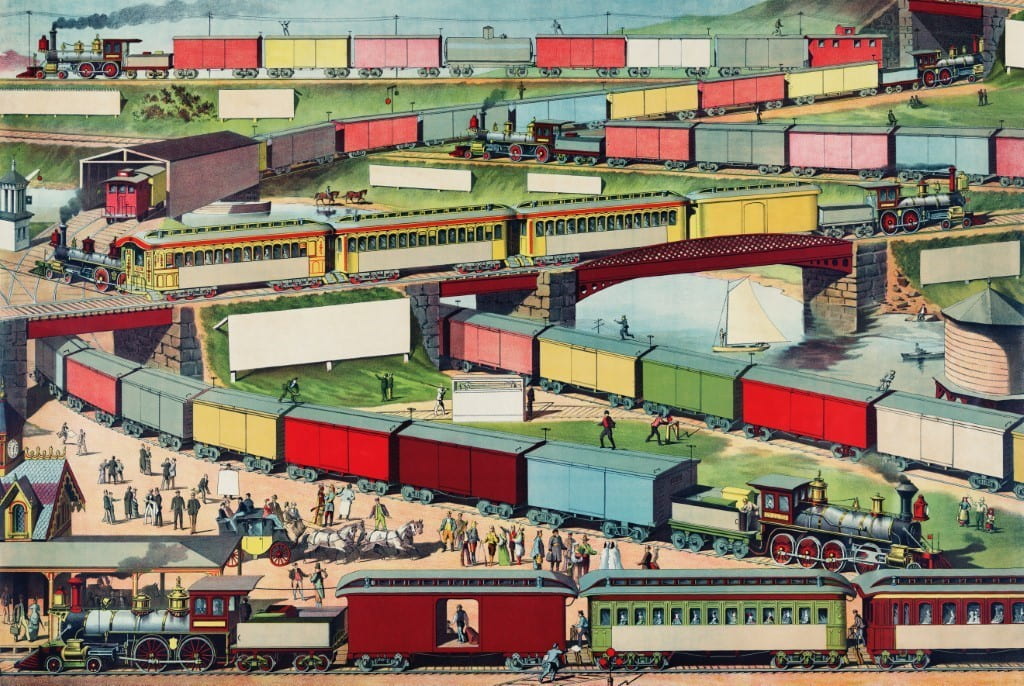

We might say that much of art engages with an interplay between the socially defined world and what lies beyond it. Much art represents a conversation between order and chaos. Take, for example, this image of passenger and freight trains by an unknown artist (Library of Congress). While at first glance, you might not say this illustration had anything to do with madness, it clearly shows an interplay between order (the lined-up boxcars, the straight lines) and chaos (the bright colors, threat of near collision, possibly endangered tiny human figures in the foreground).

Here are some links where you can explore these questions further:

Works from the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art University of Oregon

The following works of art are from the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art physical collection, online collection, or exhibits.

The Creative Growth Center

The Creative Growth Center in Oakland, California, provides a space for artists with disabilities:

https://creativegrowth.org/artists